New-Modality Drugs Behind Today’s Big Headlines

How advanced therapeutics are solving “undruggable” biology and creating industry’s most valuable assets

A lot has been happening lately across biopharma spanning massive deals and landmark approvals. Madrigal Pharmaceuticals has signed a $4.4B agreement with China’s Ribo Life Science to co-develop six preclinical siRNA therapies targeting metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis (MASH). Earlier, during the JPM week, AbbVie announced a $5.6B deal with RemeGen for a PD-1xVEGF bispecific antibody aimed at treating solid tumors. Meanwhile, Eli Lilly acquired CAR-T developer Orna for $2.4B, and the FDA approved the first oral GLP-1 therapy for weight loss, developed by Novo Nordisk.

At first glance, these headlines span different companies and medical areas. But they share a common thread: each centers on advanced therapeutic modalities (ATMs)—a new generation of medicines that go beyond the limits of conventional drugs.

According to BCG, eight of the top ten best-selling biopharma products in 2025 are new-modality drugs, and the global pipeline value for these therapies has reached $197B. ATMs are becoming a more established part of the industry and are noticeably contributing to its growth.

In this issue: Reject Tradition, Embrace Modernity — A World In Between — Antibodies — Proteins and Peptides — Cell Therapies — Gene Therapies — Nucleic Acids — Targeted Protein Degraders — Lookahead

Reject Tradition, Embrace Modernity

Small molecules (with molecular weight of 300-500) have been a major therapeutics class for over a century since the release of Aspirin in 1899, largely due to their ability to cross biological barriers and target a wide range of biological pathways. A key advantage is their oral bioavailability, allowing convenient tablet-based administration—often replacing injectable biologics, as seen with HIF-PH inhibitors substituting for erythropoietin in renal anemia treatment.

They are also chemically accessible and modular, allowing rapid structural optimization and systematic synthetic improvement. Prodrug strategies can enhance properties like solubility or enable targeted and controlled activation within specific tissues. Small molecules also, typically, have strong shelf-life stability and are compatible with diverse formulations and routes of administration, making them versatile and practical therapeutic agents.

Despite versatility small molecules pose a few challenges in drug development:

Since small molecules may bind to more than one target, they demonstrate a lot of off-target toxicity

Certain targets like large proteins might not have the designated small molecule pockets hence they can’t be inhibited and are deemed “undruggable”

With the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003, the drug discovery community expected the new genetic insights to validate key disease targets, including those once considered “undruggable.” This also underscored the need to better understand disease biology and develop new ways to tackle challenging targets beyond traditional small molecules.

Since then, progress has been gradual but steady, with emerging modalities like RNA therapies, targeted protein degradation, covalent inhibitors, next-generation peptides, antibodies, and conjugates, all now proving their way through clinical development and regulatory approvals.

A World In Between

This is how ATMs differ from traditional small molecule drugs:

Rationally designed: ATMs are engineered around known targets (often with genetic payloads), speeding early discovery versus long small-molecule screening cycles.

Modular: Components can be swapped quickly (e.g., new mRNA sequences or payloads in the same delivery system).

Personalizable: Many ATMs can be tailored to individual patients (patient-derived or biomarker-driven).

More complex: They are large biomolecules or cells and often require delivery vectors like viruses or nanoparticles.

Harder to scale: Manufacturing is multi-step and often “scaled out” in small batches rather than scaled up like traditional drugs.

With that in mind, let’s take a look at today’s major ATM classes and highlight the most promising and commercially attractive therapies within each, including notable examples already on the market and others currently in development.

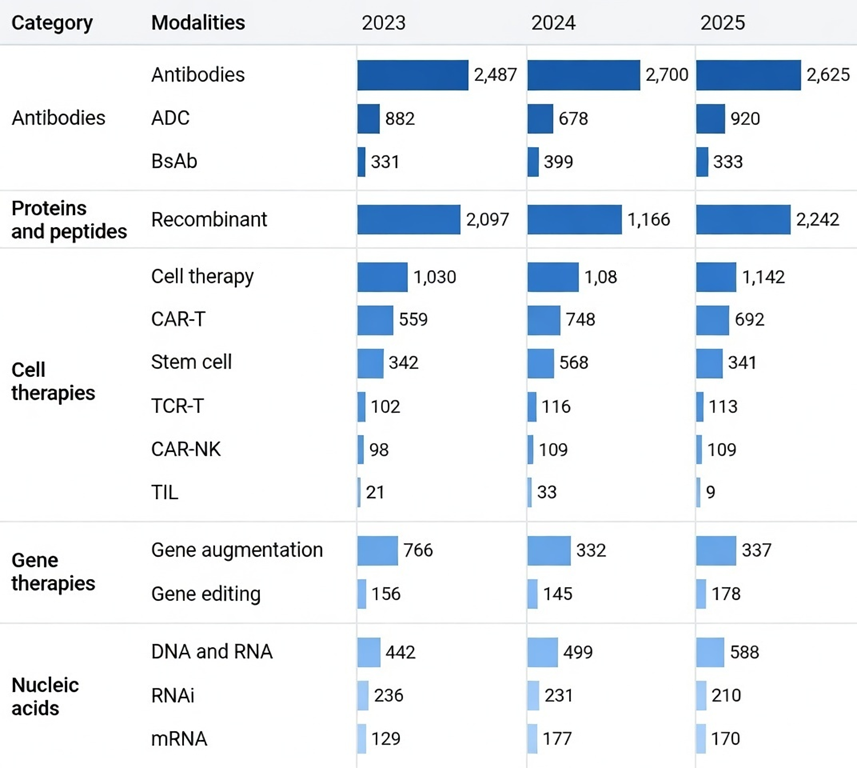

🧩 Antibodies

Antibodies (immunoglobulins) are key molecules of the humoral immune system, produced by plasma B cells to neutralize antigens and protect the body from pathogens. They act through neutralization, opsonization, complement activation, and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC). Antibody therapies can be grouped into three subcategories:

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs): designed to bind a single, specific target (such as a receptor or ligand), enabling precise modulation of disease pathways.

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs): therapies that link a monoclonal antibody to a potent cytotoxic drug, delivering the payload directly to diseased cells. while limiting systemic toxicity. Tempus has just posted their vision on the role of RNA-seq in ADC strategy.

Bispecific antibodies (bsAbs): capable of binding two different targets simultaneously, often used to bring immune cells into close proximity with cancer cells to enhance targeted killing.

➖ Keytruda (Merck)

Keytruda (pembrolizumab) is a mAb therapy that targets the PD-1 protein, boosting the immune system’s ability to recognize and destroy cancer cells. It is used across many cancer types (lung, melanoma, head and neck, bladder, colorectal, gastric, cervical, kidney, endometrial, skin, and triple-negative breast cancer), particularly those with PD-L1 expression, DNA repair–related mutations, or a high overall tumor mutational burden.

Remarkably, for the last two years in a row Keytruda has been the highest sales drug in the world, accumulating $28B in 2024 and $32B in 2025 worldwide.

➖ Opdivo (BMS)

Opdivo (nivolumab) is another mAb therapy, inhibiting the PD-1 receptor found on the T cells. Cancer cells can produce proteins PD-L1 and PD-L2 to bind a receptor on T cells and shut them down. Nivolumab blocks this receptor, stopping that “off switch” and helping T cells stay active to attack and kill cancer cells.

The EMA claims that Opdivo has displayed clinical benefit in patients with certain cancers, including melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), renal cell carcinoma, malignant pleural mesothelioma, colorectal cancer, urothelial cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and others. Opdivo’s sales rose 8% from $9.3B in 2024 to $10B in 2025.

➖ Cevostamab (Genentech)

Cevostamab (RG6160, BFCR4350A) is an experimental T-cell–engaging bsAb that binds FcRH5 on myeloma cells and CD3 on T cells. By targeting both, it aims to activate and direct T cells to kill FcRH5-positive myeloma cells. In Phase 1 studies, cevostamab has produced encouraging results in multiple myeloma.